KINSHIP SNACKS: Hand a Child a Big Sharp Knife

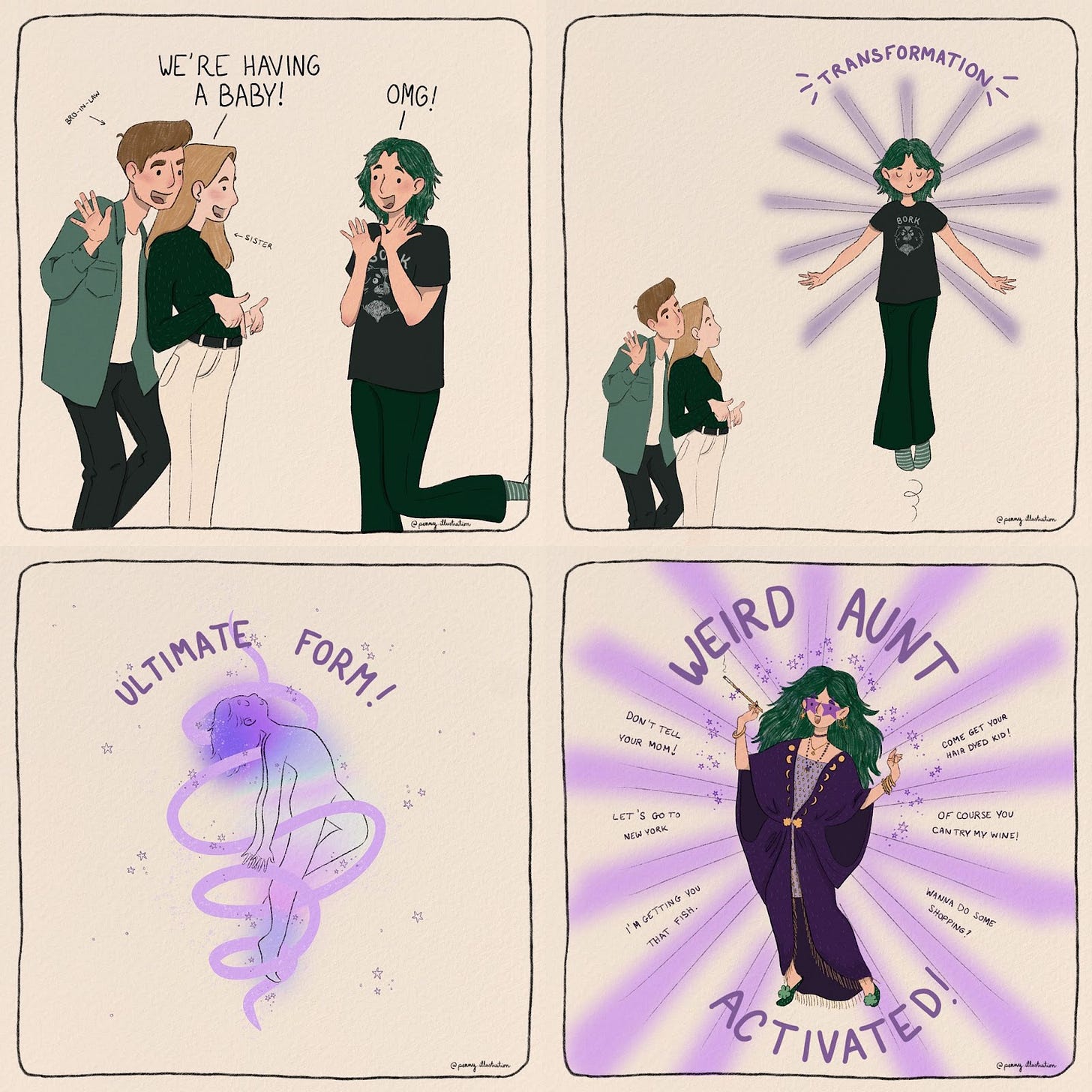

1) How to teach a kid to make a salad; 2) why building a village is hard; 3) the year in fat joy + two more recommended reads; and 4) your Cute Kid Video of the Week.

It was my sister who taught me that many (not all) small children can be trusted with big sharp kitchen knives. If you’ve been with The Auntie Bulletin from early on, you may recall that my sister is utterly awesome (if not, read about her in this early post on why I don’t play pretend with kids, and marvel at her greatness). My sister taught her older child (now 8) to use a kitchen knife when the kid was like 3. My sister would stand there and supervise and give pointers, but my niece held the knife herself, chopped the carrots herself. It had never occurred to me that teaching a small child to use a big sharp knife was a thing we could do. I marveled.

And when I myself had the opportunity to teach a small kid to use a big sharp knife, I went for it. The kids I see most often were chopping vegetables, lightly supervised, by 4, and making salads more or less by themselves, more or less start to finish, by 5. In today’s how-to, I explain how to teach a small child to make a salad, including the scary part where you hand them a big sharp knife and let them use it.

First, a few caveats.

Caveat 1. Not all kids should handle big sharp knives. You have to know the kid. Do they have a baseline sense of self-preservation? Do they tend to focus or to flit? Focused self-preservers (like my sister’s older kid) are good with knives. Flitting little sprites with no sense of their own mortality (like my sister’s younger kid, bless her) are not. Use your good Auntie judgement.1

Caveat 2. Some parents may not want us to teach their children to use big sharp knives. Again, you have to make an informed judgment call. On the one hand, occasional incuriosity about parents’ preferences is a timeless Auntie tradition. On the other hand, violating parents’ actual boundaries is not cool. When in doubt, ask. And if their answer is no, honor it – full stop.

Caveat 3. In order to teach a child to make a salad, you yourself must already know how to make a salad. In particular, you need to be comfortable wielding a kitchen knife. If necessary, teach yourself first. The internet is full of tutorials.

Caveat 4. Teaching a child to make a salad will take at least four times as long as simply making the salad yourself. Even when the kid gets to a point of relative self-sufficiency in salad-making, they’ll take at least twice as long as you do because first they will need to play with the salad spinner, and then they will need to play with every piece of bell pepper, and other random wacky delays will also inevitably arise. Budget time accordingly.

Okay, last thing: any time we’re teaching a kid (or an adult) a new skill, we can and should implement what education researchers call “scaffolding” — or if they’re being really fancy, they might call it “graduated release of responsibility.” Basically, this is about starting out by having the learner do just the easy parts, and over time teaching them to do the harder parts until they can do the whole task themselves. So when you’re teaching a kid to make a salad, you can start out with a few parts of the task (washing vegetables, or chopping just the bell peppers), and over time build to where you can do a quick safety review, point them to their supplies, and walk away.

Today’s recipe is a go-to in my household: greens (we usually do romaine + maybe pre-washed baby spinach or arugula), sweet mini bell peppers, carrots, apple, maybe some cilantro or green onions, and a simple vinaigrette. But you do you.

Materials

A stool or kid-height work station

A salad bowl

Another bowl for kitchen scraps

A big kitchen knife, properly sharpened (smaller is not better, and duller certainly isn’t better)2

A salad spinner if you have one, or a clean dish towel if you don’t

A mason jar with a tight lid, for the salad dressing

All the fixings for your salad, laid out in roughly the amounts you want the kid to use

Step 1. Teach the kid to wash the vegetables

Have them wash all the produce except the greens in the kitchen sink, however you usually like to do it. They should be pretty capable of this already since they already know how to do things like wash their hands. If the produce is visibly dirty, show them how to scrub till it’s clean. Practice tolerance of your floor and counter getting wet. Have them dry off the veggies and set them aside.

Then have the kid fill the bowl with cold water and swish the greens around until clean. Get them to dump out the water, then put the greens in the salad spinner and spin for as long as they want. Kids love salad spinners. If they ask you when to stop, tell them, “It’s your salad – stop when you think it’s ready.”

Don’t have a salad spinner? Have them lay out the greens on a clean dish towel, help them fold up and hold the edges of the towel so no greens will fly out, and send them outside or into the bathtub (curtains closed) to whirl the towel around until – in their judgment – the greens are ready for the next step. If anything, they’ll usually overdo it, but if the greens aren’t dry to your liking, have the kid spin or whirl some more. Your goal is to teach them to make an actually decent salad.

Step 2. Knife safety lesson

Whenever you are teaching a kid to do something grown-up, make a big deal out of it. “Oh my gosh, this is IT. You are about to LEARN. TO USE. A GIANT. KNIFE! Are you READY?? Can you HANDLE IT???” Get them pumped. Both of you must recognize that this is a major moment. Feel free to play some ceremonial music, although you’ll probably want to turn it off when it’s time to focus.3

Now demonstrate how to use a kitchen knife. Don’t let them hold a knife yet, but do narrate what you’re doing the whole time. When kids are first learning, you can do the initial parts for them, like chopping the top off the mini sweet bell peppers and splitting them down the middle. Then demonstrate how to take the seeds out and dump them and the tops of the peppers in the kitchen scraps bowl. Demonstrate how to chop the peppers into strips, or however you normally do it. Show them how you hold the knife, whether you pull it toward you or push straight down, or maybe you push down with your free hand on the back of the knife (with bell peppers, I’m a puller-towarder), and most importantly, show them how you keep your fingers out of the way. Dramatically ask, “What might happen if my fingers get too close?” Allow them to describe the potential consequences. Together, contemplate the prospect of bleeding all over the kitchen and having to have MULTIPLE BANDAIDS or even GET STITCHES. Children have a healthy fear of stitches. Use it.

If you have any cautionary tales about kitchen knife mishaps, now is the time to bust them out. I once took a significant slice off the inside tip of my left pointer finger while chopping kale, and now my finger is forever slightly misshapen and I am sometimes known as Lisa Weirdfinger (or, by my aunt who likes that I have a Ph.D., Dr. Weirdfinger). This type of story is appropriate to tell a small child before you hand them a sharp kitchen knife.

On the other hand, you can also consider together how, if they do get a cut, it probably won’t be that bad. They’ll have to put on a bandaid and then maybe they’ll go right back to chopping vegetables, which is what many of us do when we get sliced in the kitchen. It’s not the end of the world. In fact, the occasional cut is a chef’s badge of honor, as well as a reminder to be careful.4

Finally, review the whole safety lesson again. Then do some more fanfare along the lines of, “Are you READY? Isn’t this EXCITING??” Then tell them that you’re about to hand them the knife, but they can’t start cutting until you say so.

Step 3. Hand a small child a big sharp knife

Get them to show you how they’re going to hold it. Correct anything that needs correcting. Have them show you how they’re going to hold the bell pepper and where they’re going to put their other hand. Correct again as needed.

“Okay, now do your first chop, then stop right away!” Discuss additional corrections, but also offer encouragement. “You are chopping vegetables! This is so awesome! Your first salad!” Supervise carefully.

Repeat the process for each additional ingredient, playing up the gravitas. “Okay, now we’re doing carrots. Carrots are a whole ‘nother thing. Are you ready for carrots?” Take the knife back as needed for further demonstrations of safety and technique. “First you cut off the ends. Then I’ll cut it down the middle for you so it lays flat.5 Now you do the slices, like this.” Provide guidance on how big or small to cut the pieces.

If the kid isn’t focused enough, tell them great job, finish making the salad yourself, and try again in a few months. If they’re doing well, use your judgment to decide when you can take a step back and work on something else (keeping an eye out, of course). Say: “Let me know if you want help!”

Step 4. Have them throw everything in the salad bowl

Teach them that the greens go on the bottom and the colorful stuff on top. Teach them to notice if anything looks too big, and to pull it back out and give it another chop. If they ask, “Is this enough?” again deliver the line about how it’s their salad and they decide what’s enough (within reason). If they ask, “Can I eat this?” tell them yes, eating the dinner ingredients is the right of the chef.

Optional Step. Teach them to make a basic salad dressing

In my household, we do three parts olive oil to one part balsamic, plus at least three shakes of salt for every one shake of pepper into the salad dressing jar. Teaching a child to pay attention to ratios is slightly complicated in my experience,6 so I often make the dressing while they’re chopping, or I pre-measure the ingredients and just have them be the one to dump everything into the jar and shake it up. Then we decide together whether we should pre-dress the salad or have people put on their own dressing at the table. It varies, depending on our mood. Sometimes we also sprinkle on a little Maldon sea salt, for fanciness.7

Final Step. Serve

When the salad lands on the table, ask everyone, “GUESS WHO MADE THIS SALAD?” Make a big deal. Ask the kid how it feels to be someone who knows how to use a big sharp knife. Ask them how it feels to be an official salad-maker. Celebrate their accomplishment, and then have them make the salad again next time. The more times they make a salad, the less involved you need to be. With one of the kids in my life, I can just point her toward her supplies and leave her to it.

Wait, why are we doing this again?

Teaching a child to make a salad is fun. Teaching a child to make a salad is practical. Teaching a child to make a salad is impressive, and Aunties love to be impressive. But in my book, teaching a child to make a salad is also an enactment — in its own quiet little way — of the radical politics of Auntiehood. When someone other than a child’s parent expends the time and attention to teach that child a valuable life skill, we are helping share the parents’ load that tiniest bit. We’re showing kid and parent alike that we are invested. Indeed, we’re shouldering a little sliver of the responsibility for the raising of that child, and by so doing we’re disrupting the nuclear family model that expects parents to fend for themselves.

I even think being a little impressive serves our radical political purpose here. Because once in awhile, we might feel pretty proud of ourselves and crow about our accomplishments. The kid might say, “my neighbor taught me to use a big knife and now I know how to make a salad all by myself!” Or I might say, “yeah, my neighbor kid makes our salads all the time, including cutting all the vegetables.” And someone hears that, and they think, “hey, maybe I could do that.” And pretty soon they’re teaching their neighbor kid to make a salad, the gospel of teaching kids to make salads is spreading, and the habit of taking care of other people’s children is spreading along with it. And these tiny steps are part of how we build a world.

From the Mail Bag

New feature! I get so many excellent messages from Auntie Bulletin readers. Sometimes they’re in the comments. Sometimes they’re DMed in the Substack app. Sometimes they come to my email (auntiebulletin@gmail.com). Very often, I find myself wishing all you Aunties could read and think about them. Henceforward, I’ll be sharing gems every week (although I’ll never publish your words without your permission). Today’s is from a close parent friend of mine – her reaction to one of last week’s recommended readings, which she did not like one bit.

The article was “I’m Starting to Think You Guys Don’t Want a Village,” from Clare Haber-Harris via Slate. Haber-Harris argues that lots of parents claim to want a village, but they don’t walk the walk. Indeed, when invited to gather, parents “repeatedly reveal their preferences. They are ‘too busy’ to meet people. Things are ‘crazy over here’ and they’re ‘going out of town.’” The reason for this, according to Haber-Harris, is that parents want perfect, bespoke communities where everyone behaves as they wish.

While I felt like this article was too hard on parents, I shared it because I appreciated the author’s point that real communities aren’t perfect. But then my friend sent a long message that complicated my understanding of Haber-Harris’s argument and helped me to remember that elevating critiques of parents is pretty much never worth it. I so appreciate my friend reaching out to me, and I wanted the Auntie Collective to hear what she has to say as well.

A Parent Responds to “You Guys Don’t Want a Village”

First, some people can't tolerate a village. But how does a person get there mentally and emotionally, to tolerate only people who agree with them? I would argue that people who can't tolerate a village are themselves suffering immensely. So let's retract any assumption of ill will, and consider how someone would get to that point.

Second, while some parents are village-averse, so many others are not. Our homeownership, property, housing affordability, zoning, etc. systems are working actively against community-building, as is our lack of a social safety net and the underfunding of public institutions. I believe that the need to exert control over our lives is a strategy to avoid risk. When parents feel invisible in our social systems, and our energy is so limited, we need to reduce risk just to make it through.

Third, many people in parents’ lives are super judgmental and don't understand the context of what we’re dealing with. On top of being maxed out energetically, we have to then do additional labor to convince them to understand what we see, because they will not see it themselves. At least one and maybe both of my kids have ADHD, sensory processing issues, and anxiety. But a lot of non-parents don't understand what it's like to raise someone with those high needs; they don't understand that those needs even exist – I had never heard of sensory processing disorder until I had kids – and instead they communicate judgment. I recently had an Auntie figure tell me, based on my kids’ behavior, "there is no way I would ever take them out for dinner." I don't take my kids out for dinner for the same reason, but do I need you to say that?

In short, a lot of people do not understand children. Before I had kids, I did not like or understand them. We are not socialized to understand, appreciate, and respond appropriately to the needs of children unless we have them ourselves, and when we have them it is an insane crash course with an outrageous learning curve. We are doing our best trying to learn this job in incredibly stressful and unsupportive circumstances. Add to that issues like neurodiversity (both of parent and child) and your own childhood trauma (which many people are not aware of until the very moment they have children), and the conditions are even more difficult to convey to a new Auntie, let alone a village. I've heard a lot of "your kids are a lot," but rarely (except from you, Lis), "that looks really hard, how can I help? Tell me more about what is going on with them." I don't have enough energy to deal with my own stunted growth, my partner's stunted growth, the growth of my children, and the stunted growth of a potential villager. Often adding a villager means helping them grow up and not be an asshole to you or your kids.

I truly do not have time to socialize with anyone because I am an introvert who is trying to heal from childhood trauma and I have two kids and a full time job. I'm not an asshole, I am simply drowning.

Huber-Harris writes:

In real life, the ‘village’ includes your aunt who has what you think are bad politics, your mother-in-law who calls your 2-month-old son a ‘ladies’ man,’ your father-in-law who always has the TV on, your sister who asks too many personal questions, and … like, honestly, your 14-year-old neighbor who wants to get babysitting experience. It’s fine to decide you don’t want help from these people, but the village has traditionally meant ‘the people around us,’ not a bespoke neighborhood you might curate in The Sims.

We parents know this. The vast majority of us have nuclear families. In fact, I think we know it better than most people without kids. Because we live with people who say all kinds of crazy, mean, horrible shit to us and treat us poorly everyday – our kids. Have you seen the memes about how having a kid is like living in an abusive relationship? But we all figure out how to live with and tolerate and love them for obvious reasons. Who here is actually creating a bespoke neighborhood? It's people without kids. It's people who don't have to socialize with anyone they don't want to, because their kids are not forcing the relationships. There are countless people in my life now – school community, kids friends' parents, etc. who I would not have chosen, but who I now tolerate and even love.

I love this. Many thanks to my lovely friend for her courage and insight. Tune in to next week’s Kinship Snacks for more wisdom from the Aunties and those who love us!

Three Recommended Reads

One. Have You Taken an Airplane?

Olivia Vagelos has a newsletter called Designing for Feelings, and she had me at the name. I’m not sure what it means – although I’m learning – but I’m pretty sure I like it. Recently, she posted a lovely set of instructions for convincing people who are disembarking an airplane to stay seated a minute longer and make way for those with tight connections. It matches what I learned about wrangling large groups of teenagers back when I was a high school social studies teacher. And there’s wisdom here for all kinds of scenarios in which we want people to actually take care of each other – not merely intend to.

Have you taken an airplane?

Yesterday, perhaps? Or last week? Or two months ago?

My guess is that if you have, you have experienced this very moment that we had sitting on the tarmac in San Diego on Friday.

The plane lands and a nice, if slightly frazzled, person gets on the intercom and says:

“Welcome to blah blah blah. We’re almost at the gate. And, we have some folks who have a close connection, so if you could please let them get off first that’d be wonderful.”

The plane puts on the brakes. The seatbelt light goes off with a ‘DING,’ and every single person immediately stands up and bum-rushes the aisle.

And there’s not a chance in hell that the person in the back with the tight connection is getting off anything but dead last.

This has happened on every single flight I have ever taken in my life.

Except for one.

Two. Raising Empowered Girls in a Misogynistic World.

At her wonderfully-titled newsletter Is My Kid the Asshole? Melinda Wenner-Moyer recently interviewed clinical psychologist Jo-Ann Finkelstein about her book, Sexism & Sensibility: Raising Empowered, Resilient Girls in the Modern World. There is much wisdom here for parents and Aunties alike. The issue of what teen and tween girls wear, for instance, is one I often struggled with as a high school teacher. It was hard to know how much to try to intervene when my students wore very revealing clothing – or what to say if I did.

In your book, you talk about how parents might want to conceive of and respond to girls’ clothing choices. One thing you wrote that I found surprising was that when tween and young teen girls choose what we consider “sexy” clothes — crop tops and short skirts and the like — they’re often not actually doing it to attract attention from boys. Can you talk about why they wear these clothes, and how we should talk to them about their clothing choices (if at all)?

It's true. Most girls, especially when they’re younger, aren’t exposing their bellies, butt cheeks and cleavage to attract attention from boys. They’re interested in being fashionable, not sexy, and skimpy is what teen brands are selling. When we call attention to their clothing choices, they feel sexualized by us and become self-conscious and defensive. But, those who do purposely sexualize themselves, often do it as a way of taking control of their bodily autonomy in a world that relentlessly sexualizes them against their will. Rather than debating the dangers of their sexuality or assuming you know why they’re choosing to dress a certain way, be curious about it.

We don’t want to shame our kids for embracing their budding sexuality, but we also know seeing themselves through a system that values young women packaged for the marketplace of male desire leaves little room for pimples or tummy rolls. How can we help them see society is pushing them to overemphasize their sexuality? As the mother of teens and a therapist to many adolescents over the years, I’ve found the only “answer” is ongoing conversation and encouragement to think critically about cultural messages. As I once said to my daughter, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar but a crop top, dieting, or Brazilian wax is never as simple as free choice.

Liking how you look as a girl in this culture is practically a revolutionary act, but it’s nearly impossible to tell the difference between what we’re doing for ourselves because we want to and what we’re doing because we feel as if we have to in order to appear acceptable to others….

Three. The Year in Fat Joy.

Speaking of liking how you look, over at her wonderful Burnt Toast newsletter – one of the first Substacks I ever knew about or subscribed to – Virginia Sole-Smith reviewed the year in fat joy. Burnt Toast is an “anti-diet, fat positive community about body liberation,” and it has been both incredibly healing for me personally (in my ongoing effort to learn to like the way I look), and educational for me as someone who wants to live a world that’s fair, welcoming, and accessible for all. If the idea of “fat positivity” doesn’t sit right with you, I invite you to subscribe to Virginia’s newsletter and give her (highly informed and research-based) perspective a fair hearing. Read it for three months in 2025 and see what you think!

Meanwhile, what a wonderful roundup of fat joy she has put together. Any list that kicks off with one of the most delightful, hilarious, loving television shows ever – i.e., Somebody, Somewhere – is a good list in my book.

This show has had my whole heart since its first season, and I’ll leave it to true Midwesterners like Lyz Lenz to explain its brilliance. But on the fat rep front, I will say: This is the rare show that centers a fat woman without making the show have anything to do with her weight…until Episode 3 of Season 3, when Sam experiences the kind of thoroughly normalized, mundane, medical anti-fatness in exactly the way millions of us have experienced it. It’s a deeply authentic, understated, and nuanced portrayal of what happens to fat people in the doctor’s office and weaves beautifully into the rest of the storyline without becoming the entire storyline.

The Burnt Toast 2024 fat joy round-up also includes Nicola Coughlan in season 3 of Bridgerton, Kate Manne’s National Book Award-nominated Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia, and Moo Deng.

Coming Attractions

This Friday at The Auntie Bulletin, I’m writing about why sensitive, neurodivergent introverts make great Aunties (it’s me, hi! 👋).

Next week’s how-to is about what to do if a kid gives you something they made for you… and you don’t know what it is (just in time for Christmas!)

And in January, at long last, I will share the absolutely, positively, #1 best way to decide if you want to have kids. I’ve been saving it for after the holiday season because I want to make sure it doesn’t get lost in the shuffle. I’m hoping this one will be a good resource for a lot of people.

And Now, the Cute Kid Video of the Week

Behold a small child wielding a large knife. Is this knife sharp enough? If I had to push that hard to get through a pepper, I would go sharpen my kitchen knife, but also I’m a lot stronger and heavier than a preschool-aged child, and I have more fully developed motor skills. Who can say? But sharp knife = less likelihood of the knife slipping and related accidents.

What a delectable sandwich, meanwhile! And what is this panini-press in a toaster contraption? Has anyone used one of these? Please enlighten us in the comments!

Nothing Sold, Bought, or Processed

The Auntie Bulletin is an ad-free, anti-capitalist publication that will never try to sell you anything and receives no money from affiliate links. I can only offer it if readers like you voluntarily make modest donations to keep the lights on. This newsletter does not have a paywall, and I’d like to keep it that way. I ask that if you appreciate what you read here, you take a few seconds right now to become a paid subscriber. It’s affordable at only $5 a month, and it allows everyone to be able to access The Auntie Bulletin, regardless of their income.

Who is an Auntie, you ask? Can a man count as an Auntie? Can a grandma? Can a step-parent? Yes, yes, and yes! Check out my recent post entitled Who is the Auntie Bulletin For?

You can buy various kinds of kid-sized safety knives in stores or online. I’ve heard that people like them. For me, though, if I know a kid can focus (more or less) and heed their own basic safety, I opt for the adult kind.

Making a big deal (up to and including ceremonial music) is suitable for the introducing many life skills. See also: riding a bike, driving a car, doing laundry.

Once at my house a kid got cut twice in the same salad, and she was very proud. She was also more cautious after that.

Doing the first cut yourself is a good idea for anything hard and round, so it won’t roll around while the kid is chopping. See also: apples, potatoes, radishes.

Now that I’m thinking about it, actually you could have the kid hold the salt shaker in one hand and the pepper shaker in the other, then show them: “ONE, TWO, THREE on this side, then ONE on that side, then ONE, TWO, THREE on this side again!” A lot of kids could handle that.

I often also add toasted nuts or seeds on top of my salads, but I don’t usually involve kids in that part because it involves a cast iron pan on a hot stovetop, and I’m much more worried about burns than cuts. So I guess when I said, “a salad, start to finish,” that was slightly false advertising. 😬

So many things are best taught by aunties and grandparents--like using a sharp knife or building a fire or sewing. Driving for the big children! People who don't have to ration their patience so there's something left over for bath and bedtime for the rest of the week.

And I appreciate the counterpoint to the village article. It's true. A lot of the time the village is less welcoming of families than families aren't welcoming the village.

The knife wisdom here is brave and spot on for all ages, especially the daring news about the paring knife.