Interdependence is My New Retirement Plan

Will I wind up dying alone in a leaky tent under a freeway overpass? Stay tuned for the next 40 years and find out!

I Failed, and Thereby Learned a Valuable Lesson

Friday’s post — i.e., this post — was sent out accidentally paywalled at the VERY TOP with BARELY ANY PREVIEW and almost nobody got to read it unless they have a paid subscription! (Paid subscribers, I see you and I love you and you are doing everything right in life). Then I attempted to rectify the situation by sending out an email to all subscribers explaining that I had accidentally paywalled Friday’s post but here’s the link and now please read it! Yet mysteriously, barely anyone did.

I was like, “I have failed. I worked so hard on this post and it’s a real statement of something and I wish a lot of people could read it, but now I’ve tried TWICE to get it in front of the vast majority of Auntie Bulletin readers and failed both times, and surely I cannot litter their email inbox with yet another attempt.”

THEN I figured out that when I attempted to email the entire list of approximately 5000 subscribers I only managed to select the first page worth of email addresses and the second-attempt email only went out to 50 people. (Most of whom seem to have opened it! Readers who have subscribed since June 5, I see you and I love you and you are doing everything right in life!)

So, okay, double-edged sword. On the one hand, two failures to send one measly post! Way to technology, Lisa! But on the other hand, this all means that most of y’all didn’t get a shot at reading this post at all, so I hereby give myself permission to try one more time.

Much appreciation to those of you who are handling surplus Auntie Bulletin messages with grace, poise, and a willingness to not unsubscribe. And if you’re a paid subscriber AND you’ve subscribed since June 5, this is round three of your receiving this post and you have my sincere apologies. But boy are you doing everything right in life!

The valuable lesson I learned was: Never Make Any Mistakes.™️

It Was Father’s Day on Sunday

Happy recently-Father’s Day! In celebration, I’m removing the paywall on this post from last year about cultivating the practice of handing the baby to the dad. Love dads! Smash the patriarchy!

Also in appreciation of fathers, check out these excellent posts from dads on Substack.

Daniel Lavery (The Chatner), “A Brief Account of the Crimes Committed by the Baby”

Kevin Maguire (The New Fatherhood), “The Unbearable Lightness of Bandit”

Garrett Bucks (The White Pages), “How to Talk to Your Sixth Grader about Why Our Country Doesn’t Love Its Children”

Now Let’s Get to It

In early spring, three disruptive things happened in my life around the same time: my dear friend Chris died, I started a temporary, part-time job that turned out not to be quite so part-time, and out of the blue someone asked me to apply for the permanent, full-time job of my 2021 dreams – a job that would be great and stabilizing in so many ways, but wouldn’t allow me to continue with The Auntie Bulletin. Between grief, overwork, and confusion about what I wanted professionally, I slowed the newsletter to once a week and have been sort of treading water for the past few months. (Thanks for not unsubscribing in the meantime!)

Now the season is turning, and although it’s not quite solstice yet, it already feels like summer here in the Pacific Northwest. We’re having a lot of sunny days, I feel like I’ve gotten through the hardest part of mourning for now, and my temporary gig as an instructional coach ended last week. Most importantly for our purposes, I also decided to pass on 2021 Lisa’s dream job and stick with writing The Auntie Bulletin.

This decision was so fraught! Today I’m writing about the leap of faith I find myself taking, how I’m doubling down on Auntiehood as a plan for life and livelihood, what’s scary about it, and why I’m optimistic nonetheless. I’ll also be up front about the privileges and advantages that make my plan possible – conditions that are not available to everyone, but should be.

The job I decided not to pursue was a good job, Aunties. It’s at a university where I used to work, doing teacher education work that I enjoy, with people I genuinely like and respect, for a decent salary with good benefits and a continuing contract. Believe it or not, I actually helped write the job description back in 2021 when I wanted the department to create this position and hire me for it. They wanted to hire me for it, actually, but they didn’t have the money then. Now, miraculously, in the midst of a university-wide hiring freeze, at a time when the federal government is actively defunding and attempting to dismantle higher education, this scrappy little university department that I really love found the budget and reached out and asked me to apply for this job that I once longed for.

And I said no!

I said no because this job is non-negotiably full time (really, it’s full time plus), and I have a chronic health condition that means I can’t actually work full time no matter how much I keep trying to. When I work full time, I am rarely able to exercise because exercising takes so much out of me, and if I don’t exercise I have more and more pain in more and more places and I also get injured a lot. When I work full time, I rarely have the capacity to be present with the kids in my life, with my family, with my friends, with my neighbors, or with the groups where I help out. When I work full time I get home from work and often have to get straight into bed. And it’s just – Aunties, it’s just not a good enough life. It’s not what I want for my one wild and precious etcetera.

The decision to forego a stable, well-paying job hasn’t been easy. As I’ve gotten older, and had more health problems, and spent more years married to a person who locates all his anxiety in financial planning, and been through seasons of life where I had to shop around for long term care facilities for my elder relatives, I’ve become downright financially worried. I’ve gotten pretty tangled up in the belief that I need to hoard a lot of wealth so that I can be housed and cared for in my old age.

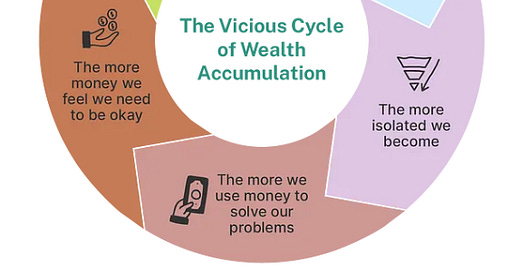

Okay, but let’s talk about the prescribed wealth hoarding model in the United States, otherwise known as prudent financial planning (supposedly). The conventional advice from financial planners is that people of my age are supposed to accumulate something like $1 million in order to retire. Or maybe $1.5 million.1 In case you’re not hip to the logic here – I wasn’t until I married a very specific kind of nerd – we’re supposed to amass so much wealth that we can live off the interest and dividends until we die. It’s not enough to save what we’ll need to make it to the end of our life; we need (ostensibly) way more than that. We need to accumulate so much wealth that we can live off the wealth that our wealth earns. We need – we are told – enough that we never have to touch the principal, and we can pass our wealth along to our next of kin, whoever they may be.2

Sounds nice if you can manage it, Aunties! But good luck: Dana Miranda reports that even baby boomers have saved only 12%, on average, of what they expect to need in retirement, and they’re the generation that’s supposed to have had a relatively easy time of it, financially speaking. Almost half of American workers have no access to an employer retirement plan at all, or else they can’t afford to contribute to one. “All of us face a future with ever-increasing costs, ever-shrinking social supports and tenuous access to even private insurance,” Miranda writes. “So who, exactly, is retirement planning advice for if no one can follow it?”

If you’re among the lucky, diminishing few who are able to follow financial planners’ retirement advice, that’s awesome! I’m so happy for you! You should upgrade to a paid subscription to The Auntie Bulletin!

As for the rest of us, what can we do to seek security in our old age? Of course, we can and should advocate for policy changes that support workers and allow us to save for safe, comfortable retirements. Raising the income cap for Social Security could secure funding for that program long into the future. Strengthening union protections could allow workers to organize and win back the employer-funded pensions that have been eliminated in most industries. Enacting comprehensive universal health care would help all of us access care in our old age or when we’re sick, regardless of financial situation. Getting the costs of housing and higher education under control would allow workers to save more throughout our lives.

Important as these policy aims are, though, I don’t feel like I have much of a lever over them in my daily life – especially under a U.S. presidential administration that is actively hostile to every single one. What I can do is care for the people in my communities, and hope that when I need care in turn, people will be there for me. And the more our social safety nets are chainsawed to tatters around us, the more we’ll all need to be able to rely on our neighbors and communities to ensure everyone’s needs are met.

I’ve been reading a lot of Robin Wall Kimmerer lately. She tells a story in The Serviceberry that’s become a sort of guiding star for me, about the experience of a linguist who was studying a hunter-gatherer community in the Brazilian rainforest.

He observes that a hunter had brought home a sizable kill, far too much to be eaten by his family. The researcher asked how he would store the excess. Smoking and drying technologies were well known; storing was possible. The hunter was puzzled by the question – store the meat? Why would he do that? Instead, he sent out an invitation to a feast, and soon the neighboring families were gathered around his fire, until every last morsel was consumed. This seemed like maladaptive behavior to the anthropologist, who asked again: given the uncertainty of meat in the forest, why didn't the hunter store the meat for himself, which is what the economic system of his home culture would predict.

“Store my meat? I store my meat in the belly of my brother,” replied the hunter.

I’ve been thinking so much about what it would mean for me to “store my meat in the belly of my brother” – to give to my loved ones and communities and trust that my generosity will circle back to me when I need it. I know it’s how I want to live. It’s how I want us all to be able to live.

Now that I’ve declined to interview for the good university job in teacher education and opted instead to stick with The Auntie Bulletin, I’m trading a stable monthly income and a 401(k) with employer matching for financial unpredictability and what I’ve started thinking of as the “Interdependence Retirement Plan.” And since I have a much more flexible schedule as a writer than I would as a teacher educator, I’ll be able to carry on helping out my loved ones and communities as much as I can manage – hoping that people will help me out in turn if I need it, sooner or later. I’ll keep writing about interdependence and sharing and kinship and showing love for other people’s kids, elders, and people of all ages – hoping also that an increasing number of readers will find what I write about helpful and continue to support this work by getting paid subscriptions.

Now, I want to acknowledge the privilege inherent in being able to pass up a well paying job in order to be a not-quite-full-time writer. I don’t have a trust fund, but I do have a pretty sweet long-term disability insurance benefit from my former employer, and that’s a function of having been able to access, in the past, a good job with good benefits where there was a very nice woman in HR who was willing to go to bat for me. The benefit isn’t nearly as much as I’d earn in a full time job, but it’s a lot more than I’d receive if I were on government disability. I also have a partner who worked in tech for many years and paid the down payment on our house. We both have lovely parents who are financially secure and would be happy to welcome us into their homes if we ever needed somewhere to live. We have access to plenty of credit, we’re unlikely to ever be targeted by police, and nobody will ever try to deport us. Our parents and our grandparents and even our great-grandparents could say the same.

Everyone should have it so good, geez.

Since I’m in this fortunate position, I’m thinking to make of my life an experiment in interdependence. Is it possible, since I have a bit more flexibility and security than many people, to practice generosity and have it come back to me when I need it? I’m genuinely curious to see how it goes. Thinking of my recent career decision as an experiment in interdependence makes the whole thing feel a little less scary and a little more interesting.

And I hope this experiment might benefit not only me, but you as well, and all of us. I hope to be finding out as I go along, over the coming months and beyond, that practicing generosity and hoping for timely generosity from others does indeed allow me to stay afloat financially. I’ll keep you posted. I also hope reading about functional everyday interdependence will invigorate you to keep cultivating sharing and receiving in your own life, and that the more we expand into what Robin Wall Kimmerer calls “the gift economy,” the more those around us might find what we’re doing intriguing, and want to try it for themselves.

I’ll end this post with another extremely awesome excerpt from The Serviceberry, this time from Kimmerer’s conclusion. If plant ecology is any predictor, she suggests, then the market-based economy under which most of us currently live might slowly be replaced by a more mature economy of generosity. Drink it in, Aunties, and consider that to the extent that we each find small ways to practice giving in our own lives, the transition to a more mature and loving economic system might already be underway.

In Sacred Economics, Charles Eisenstein reflects on the economy of ecosystems: “In nature, headlong growth and all out competition are features of immature ecosystems, followed by complex interdependency, symbiosis, cooperation, and the cycling of resources. The next stage of human economy will parallel what we are beginning to understand about nature. It will call for the gifts of each of us; it will emphasize cooperation over competition; it will encourage circulation over hoarding; and it will be cyclical, not linear. Money may not disappear anytime soon, but it will serve a diminished role even as it takes on more of the properties of the gift. The economy will shrink, and our lives will grow.”...

As a botanist, I know that there is guidance from the world of fields and forests. Plant communities are changing and replacing one another all of the time, and a dynamic mosaic we know as ecological succession. Far from the stereotype of the ‘forest primeval,’ plant communities are constantly in flux. From a bird's eye view the ‘unbroken forest’ is in fact a patchwork of stands of different ages and experience.

Fires, landslides, floods, wind storms, outbreaks of insects, disease, and disasters of human origin disrupt the green blanket in unpredictable ways – and yet with a somewhat predictable response. Oftentimes a major disturbance that clears the former forest creates a gap, with full sun, disturbed soil, and plenty of resources, since the previous inhabitants are now gone. Such places are colonized by fast growing species in high density, trying to take advantage of the transitory conditions. These pioneer species are opportunists, with traits that consume resources, crowd out others, and reproduce like crazy. It's all ‘me, me, me,’ investing only in their own exponential growth with no regard for the future, their relatives, or longevity. Sound familiar? It's a field of fast-growing weeds, or a stand of aspens. It's as if Euroamericans, in the age of colonization and displacement of “old-growth cultures” are behaving like colonizing plants after a massive disturbance, dominating the landscape. But those colonizing plants find they cannot continue this rate of growth and resource extraction. They start to run out of resources, disease may attack the overdense populations, and competition begins to limit their growth. In fact, their behavior facilitates their own replacement. Their rampant growth captures nutrients and builds the more stable conditions in which their followers can flourish. Incrementally, they start to be replaced.

The ones who come next are different, growing more slowly in a resource limited world. Stressful conditions incentivize nurturing relations of cooperation alongside competition. The extractive practices of the colonists must be replaced with reciprocity and replenishment if anyone is to survive. Investing in persistence, the new inhabitants are in it for the long haul. These communities have been called “mature" and sustainable, in contrast to the adolescent behavior of their predecessors. This transition from exploitation to reciprocity, from the individual good to the common good, has been seen as a parallel to the transition that colonizing human societies must undergo, from hoarding to circulation, from independent to interdependent, from wounding to healing, if we are to thrive into the future.

Related Reading from The Auntie Bulletin

Grown Ups Share

There are so many things I love about living in cohousing, but one of the very best is that the kids in my community get to regularly witness adults sharing with each other. These kids don’t just get told to share – they get to see sharing in action, over and over and over again.

Who Will Care for You in Your Old Age, If Not Your Kids?

What does it look like – what does it feel like – to have a good end of life? I hope the final years of my life will be something like what my grandmothers experienced. My dad’s mother, my Grandma Sis, died last year at age 96. In the last decade of her life, three of her five children lived within 30 minutes of her, and all five visited often....

What We Worry About is Not Death, It’s Vulnerability

If you imagine today’s interview isn’t for you, think again. If you’re a parent, you need to hear what aging is like for people without kids – including the Aunties in your life and the Aunties you hope to have. We need you to read this. If your own elderhood seems far away, take it from me – it’s going to approach faster and faster until it’s no longer approaching; it’s here.

Nothing Sold, Bought, or Processed

The Auntie Bulletin is an ad-free, anti-capitalist publication that will never try to sell you anything and receives no money from affiliate links. If you appreciate what you read here, please take a few seconds to become a paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end! You get the secret scoop that if you can’t afford a paid subscription due to financial hardship, you can reply to this email, shoot me a message in the Substack app, or email me at auntiebulletin at gmail dot com and I’ll comp you a 12-month paid tier subscription, no questions asked.

Dana Miranda explains: “Americans on average believe they’ll need $1.46 million in savings to retire comfortably…. That might feel like a big number, but at the recommended annual withdrawal rate of 4%, that would provide about $58,000 per year in income, well below the current median income in the U.S.”

Who inherits our money is a complex question for people, like me, without children. One of the key purposes of accumulating wealth in the United States and many other places is to be able to pass it on to our children and secure for them a standard of living as high as or higher than our own. But in the absence of having children, as Iris Brilliant writes, “it is rarely considered a possibility to simply share resources with non-family members who need it now.” I wonder if it’s possible for Aunties – especially non-gift-giving Aunties – to set an expectation with the young people in our lives that they are not going to inherit much money from us, and instead allocate the majority of whatever we have at our death – be it a lot or a little – to a cause we believe in, or return our resources to our local Tribes.

Beautiful post. I just read the Serviceberry a few months back and similar questions have been rolling around in my head.

I've been thinking about retirement type savings and investing in general. Many of the investments go to the large companies (because they are part of many mutual funds and are "good" companies to invest in) driving the greatest extraction and exploitation.

I don't think my wife and I will forgo any future investments but we have been talking about decreasing our retirement investing in order to do more good now. We are also in a very privileged position and in fairly good financial standing that we are also discussing eventually getting to where we can both work part time and find more ways to actively serve our community.

"Oftentimes a major disturbance that clears the former forest creates a gap, with full sun, disturbed soil, and plenty of resources, since the previous inhabitants are now gone"

I just watched a documentary about the origins of London. After the plague wiped out half the population in the 1300s, the survivors found themselves in a similar situation: fewer people in the same space, more jobs to fill, and greater opportunities for upward mobility. The aftermath of devastation created room for renewal, both in nature and in society.