Last week, I got to talk with Jessica Slice on Substack Live and it was so, so great. Jessica is a disabled parent and the author of Unfit Parent: A Disabled Mother Challenges an Inaccessible World. Reading Jessica’s book and then getting to talk to her about it has really helped me think about what it means to live in and provide care for others in the context of an ableist culture.

There’s something here for everyone. If you are disabled or sick and are trying to figure out whether you want to have kids, this conversation will be right on target for you. But if you’re not disabled, or not a parent or not trying to figure out if you want to be one, there’s still so much here for you – including some very wise perspective on how ableism makes life harder for all of us. In contrast to the ableist culture of constant hustling, Jessica writes that, “disability teaches creativity and acceptance. It rejects rabid capitalism and embraces mutual aid. It encourages rest.” Everyone I know needs these things.

I’m really excited to share our conversation with you. The video is above and a lightly-edited transcript starts now.

Now Let’s Get To It

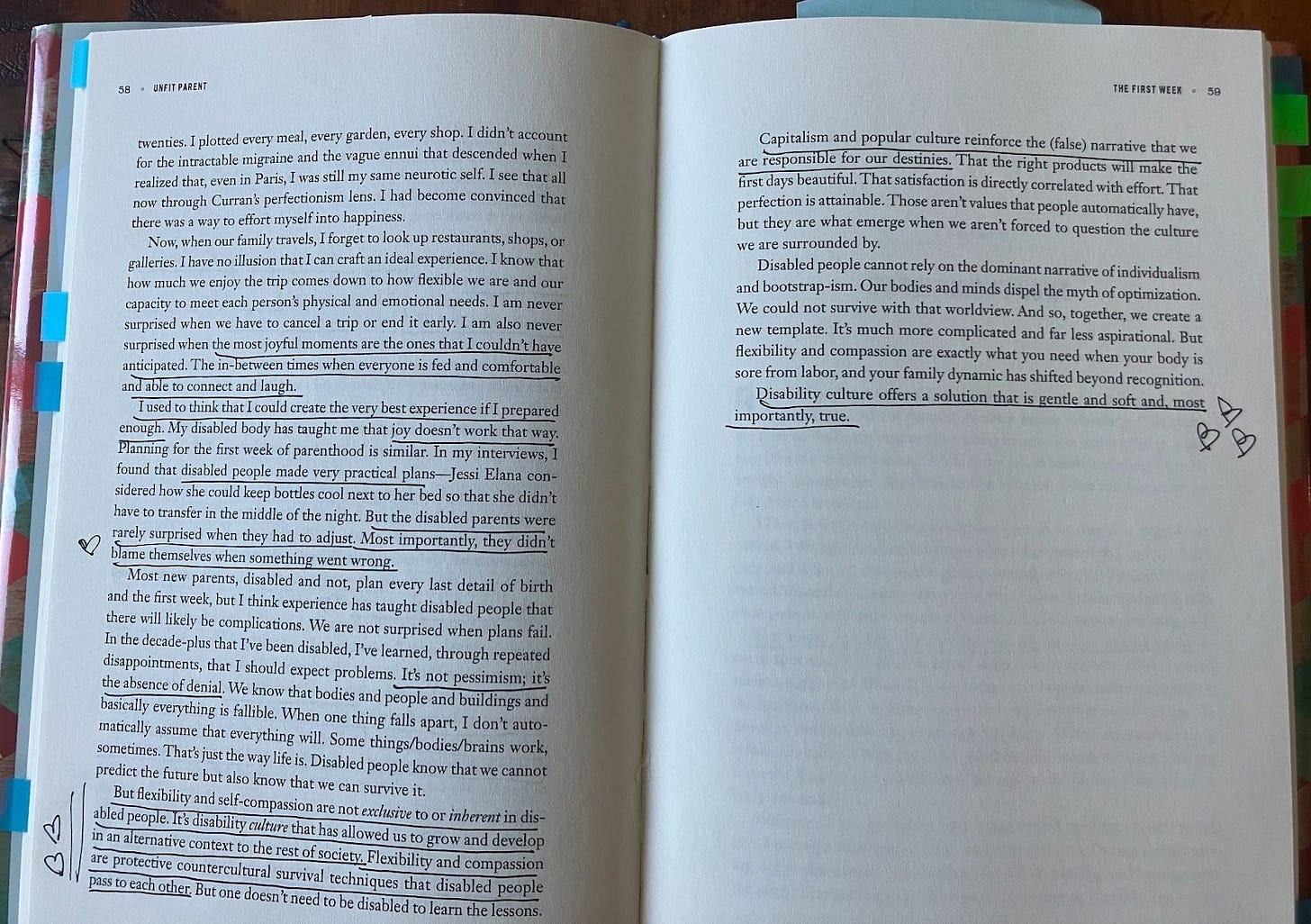

Lisa: Today I'm welcoming Jessica Slice, and I'm so excited to talk to her. She's the author of this awesome book called Unfit Parent, and I'm going to show you my copy because I just want you to see how extensively annotated this thing is. There are hearts everywhere, lots of little tabs.

Jessica is a journalist and a parent who has a disability, and everyone’s talking about her book. I feel like every time I mention to somebody that I'm interviewing you, they're like, "Oh yeah, I've read three interviews." Which is so great. I'm actually interviewing you because Anne Helen Petersen told me I have to interview this woman and put me in touch with your agent.

I'm super excited to talk to Jessica because we both have the same disability. We both have hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. It's pretty impactful on our lives. We made different choices about whether to become parents, and that's one of the things we're going to be talking about today.

One of the reasons I heavily annotated Jessica's book was that I thought this would be great for Auntie Bulletin readers. But it turned out to be a really profound reading experience for me to read about your experience of having EDS and also the strong reframing that you do around disability as an asset in our lives as opposed to a deficit or deficiency. For me, I've come across that argument lots of times and I believe in it theoretically, but reading your book, it landed for me in a way that I hadn't really fully understood before. I think partly because we have similar life conditions. So I'm full of gratitude to you.

Jessica: Thank you for having me. I'm thrilled to be here and I love your work. It was so nice of you to take the time to email to say you're liking the book. As you know, when you put writing out, it's so scary. It's easy for our brains, or at least definitely mine, to be slanted towards negativity. So if I know someone's reading a book, I'm like, “Most likely they don't like it.” So anyone saying the opposite is amazing.

Lisa: I feel you. I feel like with the Auntie Bulletin, anytime anybody tells me they're reading it, I'm like, "Really??"

Now, I don't get to talk to people with EDS that often, so this feels like a cool opportunity to talk about what our life is like. Would you be willing, Jessica, to do just a little explanation about what EDS even is?

Jessica: EDS is a difference in one of the elements of our connective tissue. It's a change in how our collagen is produced. Collagen is everywhere in the body – in joints and muscles and ligaments and organs and blood vessels. So the impact of EDS is almost head to toe. It impacts vision. For me, I have hearing loss in one ear because of EDS. It makes us more prone to injury, more prone to specific complications of those injuries. We have to monitor our heart health. Then there’s also autonomic nervous system dysfunction, which causes dizziness and nausea, trouble regulating heart rate and blood pressure, trouble regulating digestion. So it's kind of a disability that impacts everything.

I'll actually have to be adjusting during this to manage pain and discomfort. For me, the reality of daily life is a lot of pain, but also dizziness and nausea and being easily fatigued. I have these things I call episodes, which is like I'll suddenly feel terrible and have a really high heart rate, extreme nausea, this sense of doom – it's one of my more uncomfortable symptoms. But I am, without exception, managing or experiencing a symptom every moment of every day.

I can stand up for about 30 seconds and sit upright for a few minutes, but I use a power wheelchair if I'm not in my adjustable bed because I have to really be reclined and supported all the time. Or I start – if I'm trying to sit up or stand up – I start to get black around the outside of my vision. I start to get tingly, just the feeling of pre-fainting. How does that compare to your experience in your body?

Lisa: Wait, how are you doing with sitting up right now?

Jessica: Well, I'm trying to figure out how to look at this phone in a way that doesn't hurt. I think I'm just going to keep moving around as we talk.

Lisa: Yeah, keep moving around. Maybe this is something we can flag for Substack – that Substack Lives are only possible on devices right now via the app, which means that we both have to be on an app and we can't tilt our screens back in a way that we might be able to do if we were on a computer.

Jessica: Usually I can do my computer and I know the angle to do it that doesn't hurt my body. But I'm trying to be on screen and not hurt my neck.

Lisa: Just lean back and if you're at the bottom of the screen, none of us are going to mind. We're all with you. Do what you need to do.

So I would say that my experience is less impactful than yours. And there's a huge range of what people have in EDS because there are people who are incredibly impacted on a moment-to-moment basis – Jessica, I would include you among those people. And then there are also people who are barely impacted or they're so mildly impacted that they don't know that they have it, which was my condition for many years, where I would frequently dislocate my joints for no reason and just be really tired all the time. But I didn't really know what that was about. I was blaming it on myself and thinking it was a moral failing that I was tired, and I thought that I was weak and lazy and not brave. And in fact, what was happening was that when my friends were scrambling down a cliffside, they were a lot safer than I was trying to scramble down a cliffside in danger of dislocating my knees at any given moment.

When I got COVID, my symptoms got really exacerbated and that's when I got diagnosed. These days I have days where I'm really not impacted and then days where I'm very impacted. We have a number of different guests staying at our house right now, and yesterday I also went over to help my friend in her garden, which was an ambitious thing for me to do. And then I was supposed to make dinner for everybody. I got home and crashed out. I was in so much pain – I way overdid it yesterday. So I get these flare-ups that are just lots of pain and injuries and lots and lots of fatigue.

Jessica: Yeah. So will you pay the price for yesterday? How long will you pay the price?

Lisa: Probably through the rest of today. Not super long, but the longer I push myself, the longer I pay. I had a really wonderful therapist who herself has a chronic health condition. She helped me recognize that for example, when I travel, if I go on a trip for four days, then I need to book four days for recovery after that trip.

Jessica: That has absolutely been my experience. I went on a road trip recently and then I had to basically – it took me a week to recover from it. When I have to go into the red with my health for something I don't enjoy doing, that's what makes me angry for a few days after. I'm like, “that wasn't even worth it!”

Lisa: I like that metaphor of going into the red. Helping my friend garden yesterday, I made a conscious choice to do that in the hope that I wouldn't pay the cost – which was a delusional hope, in retrospect. But it's really different when I make a decision that I'm going to push myself because of something that I care about versus having to show up for something that I would rather not be doing.

Anyway, there's just a huge amount of diversity in people's experience with EDS and lots of different kinds of co-occurring conditions that people have.

So we have these similar conditions. We both also experienced infertility. You write in your book, Jessica, about being told by medical professionals that you could not have children and that it would not be safe. I lost several pregnancies and then found out later that the EDS might have been the reason for that, because we have weak collagen attachments, which means that it's harder for embryos to attach to the uterus.

So we both experienced infertility and then made different choices about being parents. I struggled with it. I didn't want to be a parent, then I decided that I did want to be a parent. My partner was on board, so we tried for several years, lost a bunch of pregnancies, explored IVF, explored adoption. And finally, I opted out. And I have been happy with that choice.

Now in your book, I was so struck by how crystal clear you were that you definitely wanted to have kids. It was just absolutely clear. So can you tell me what made you so confident that you wanted to do it and also that you could handle it?

Jessica: I don't remember agonizing over it. In my twenties, I didn't want kids because I thought I would be a bad mom. Before I was disabled, before I knew I had EDS, I was so relentless with myself that I didn't want to subject another person to me. I didn't think I'd be a good mom, just based on my personality.

It was becoming disabled that changed how I think about myself and how I think about life and days. It just changed my values, and I then did want kids.

I've been thinking about what I care about most as a parent. One is that I feel really committed to always being kind to my children. That doesn't mean not strict, it doesn't mean no boundaries, but it means that they know that I am a steady thing in their lives, that they will know what they're getting when they come to me, which is patience and consistency and kindness and happiness to see them. And the other thing that I think is really important is to tell the truth to my kids about what they're experiencing. I think what really messes you up is if you live in a house that is one way and then the people in the house tell you it's not that way.

Both of those things are very possible with my disability. I am very limited in what I can do with my kids, but I never tell them it’s not happening. I say, "I'm very tired," or "My back hurts," or "My hip hurts," or "I need to rest. Can we do that in bed?"

So the thing I feel like would be in conflict is if I felt like I needed to pretend to be invincible with my kids, and then I couldn't be a disabled parent because I would have to lie. But I don't think I need to be invincible. And then also, in order to stay kind, I need to not push myself too much, which means not being able to do everything that they would want me to do or not being able to do everything I want to do. I am okay with that. For me, the onset of disability brought such clarity about what I care about.

Lisa: And do you feel like you anticipated that ahead of time – what you would care about, or just that you would be up to it? I had so much fear like, "I'm tired all the time, how am I going to keep up with kids?" I really appreciated your clear perspective. Like, "This is going to be fine." And I suspect that this ties into your really lovely and important argument that you write that disability is a gift – that there's a wisdom that comes from disability.

Jessica: I knew I would be much better as a parent disabled than not disabled. I mean, I think disability is a gift, but I don't think everyone has to think their own disability is a gift. The thing I feel so strongly about is that I get to think that my disability is a gift and that it is wrong for someone to tell me that it's tragic. For many people, their disability ends up being a net loss in their life, but I don't think it's automatically a net loss. And I think it ends up feeling like more of a loss if society thinks it's tragic.

So I think we need to allow the space for people to think of their bodies the way they want to. It’s the same with fat liberation. People get to want their bodies to be how they want them to be. And if society is screaming that the way to have a good life is to have an invincible body, and then your body feels fragile, your own perception of that fragility is going to be altered by what society is telling you.

So disabled innovation and disabled creativity and community and the way it changed me – I want to provide this option to take another path.

So no, I didn't worry about not being able to parent. I think part of that is just my nature. I always think I can figure things out. It's a slight point of conflict in my household because I'm like, "We'll figure it out," and my partner's like, "But how? What are the steps of figuring it out?" It's not always an adaptive part of my personality, but it is true.

So I took that into having kids. And I will say in my defense: with my kids, it has been true. The complications of parenting my two specific children have been things I could never have imagined. And my ability to problem-solve and build a life with creativity has been more than I could have ever imagined. I have met the challenge consistently.

Lisa: I love how you wrote about the wisdom that you've gained from your disability. It caused me to start wondering, what wisdom have I gained from my disability?

And when you talk about your confidence that "we're just going to make it work," I really loved the parts in your book where you were talking about how people with disabilities really have to learn to be resourceful and also have to learn to be really flexible and have to learn that things aren't always going to go the way that we expect them to. And also we're going to get old and get sick and die and we can be chill with those things to a certain extent. Disability kind of teaches you to relax around some of those things.

I'm just really thinking about that in terms of your decision to have kids. It sounds like that perspective there, like, "It's going to be alright."

Jessica: I had already had to give up on the life I had imagined, so the thought of a child also changing my life – it didn't feel as scary.

I will say part of it was timing too. I had multiple years of having to come to terms with my disability and really grieving it and trying to get a diagnosis. There were really hard years along the way. But fortunately, a place where I have landed is that I think more clearly and that my priorities have shifted and that I feel a confidence in my ability to problem-solve and I feel an acceptance of my life in how it looks now.

But it wasn't immediate. My onset was really sudden, and if you had asked me a year after that if I could be a parent, I would be like, "No, absolutely not. I can't figure out how to get groceries." I was in a state of complete panic and I was terrified every moment for a period of time. I also had access to therapy. I had friendships. I had ways of constructing a new life and a new view of myself and a new set of values too.

Lisa: That's a hopeful and helpful perspective – that taking the time matters, right? Like, we have to work through our stuff as opposed to just being ready.

Jessica: I don't think the conclusion of having enough time and reckoning with yourself and spending a lot of time reading poetry – I don't think the conclusion needs to be kids. I think in my case it was. That was the thing I wanted. But I think the decision that feels right comes from time and acceptance of your reality, no matter what that decision is. I don't think it will automatically lead there.

Lisa: For me, it didn't. It took a long time to figure out that I didn't want to have kids. And even after I had decided, I still was reckoning with it for a while. Now I'm in a place where I'm really glad that I decided to not have kids and I can focus on being an Auntie. But it was a slow process, and I think really the goal is just to be able to arrive at some clarity and peace with whatever we have decided.

Jessica: There's also the reality that disabled people are sterilized against our will in 33 states and that many fertility clinics won't treat disabled people. If you're a wheelchair user or paraplegic or quadriplegic, a lot of OB-GYN offices aren't accessible. What I want so much with this book is to show that the choice to have kids is important. It's not the only choice, but we need the option to be available. And if a disabled person goes in for surgery and then without their permission gets sterilized, which does happen actively, that is inhuman.

We have to reject this notion that disability automatically makes us incapable of being loving, good parents.

Lisa: Absolutely. I mean, that seems to me like a good summary of the thesis of your book.

I have written a few times about my choice to not be a parent and how that has been a positive choice for me as someone with a disability. And then I've had folks comment on those posts saying, "That's a super ableist thing for you to say. As a disabled community we need to advocate for our right to have children, for our right to choose to have children, and for the perception that people with disabilities are absolutely capable of being awesome parents."

So I'm curious what your take is on this. Should I not be saying that disabled and chronically ill people might want to be Aunties instead? I honestly don't know how to think about this.

Jessica: No, I think you should. I don't think you should say we're incapable, of course. My book comes from the perspective of disabled parents, but I think there are a lot of disabled people who choose not to or, like you experienced, are unable to have kids. There are also disabled people who, because of disabilities, wouldn't be approved as foster parents, don't have the financial resources to have surrogacy, which is how we had our second kid. There are people who are in such a state of health crisis that the time when they could have kids passes. And they have tremendous grief around that.

I think there's the choice to not have kids, but there's also the people who suffer because they wanted to and couldn't. And I think any true story about disability has to include all of those perspectives. I think the perspective that's overdone is the disability as tragedy or that our children should be taken away or that our children are going to suffer because they're watching their parent be weak. I think that story is done. I think we can just not tell that story.

Bodies are so fragile and unreliable. And any true story about parenting will talk about that side of it too. It will talk about the grief or the choice. I mean, because you've had – you are happy in your choice now, but you've had periods of profound loss. And I think of course that should be shared. I think prescribing that someone else should be child-free, which you would never do, is where the problem would be.

Lisa: Thanks. That helps. And it’s making me think about the stories in your book about how disability shows up as a resource in parents' lives. You did this awesome little study talking to a bunch of disabled parents about their first week as parents and a bunch of non-disabled parents about their first week as parents. Can you tell us what you found out?

Jessica: Yeah. I mean, what I would love is for someone to really research this because I've interviewed about 50 people total and my results have been staggering. Of course, my methodology is the snowball method and it didn’t get peer reviewed or anything, it's not like a real study. But what I found is that disabled people adjust to parenthood much better than non-disabled people.

I have all sorts of theories about it. One is that the actual practical reality of the first week of parenting is much closer to a disabled life than a non-disabled life. By the time I was a mom for the first time, I had been practicing sitting in bed all day for years. I'm an expert. I'm totally fine with a tiny day where I just move from the bed to couch and back to bed.

And so major loss of freedom and adventure and this loss of identity that people go through – I think a lot of disabled people don't have that because their lives are already sort of limited.

But I think there's a deeper part of it, which is that parenting a newborn is this constant reminder, especially if you were pregnant, which I never was, but there’s this constant reminder of how unreliable bodies are. I don't know how much time you've spent with a newborn, but they are bananas. The way they eat is pure chaos. Every single bite, you're like, "Is this working? Is it working? It's coming back out.” They're burping. And then they're breathing really fast. And then it pauses. They were just inside a body, and now they're not. And you look at them and you're like, everything is fragile. You cannot avoid being reminded how fragile everything is.

And then there's the whole worry that they're about to die in their sleep. And this total confrontation with mortality is very hard for everyone, including me. But if you are in a body who has been hospitalized, who has had moments of emergency, who has had uncertainty or has had diagnostic trouble, any of that, this confrontation with sloppy bodies is not new. I think that also makes it easier.

Society tells us that it's terrible to need things and we should be independent. And caring for a newborn is such a specifically needy period of time for the parent and the baby. It's just all needs everywhere. And disability is often a forced rejection of hyper-independence. And so there are these ways that disability makes that shift into parenthood, that initial shift for the first time, easier.

This has been replicated in studies about cancer. Actually, disabled people adjust to cancer better than non-disabled people because the medical system isn't as new to us. There's been a few studies showing the rates of postpartum depression in disabled versus non-disabled people, and it's higher in non-disabled people.

None of this is saying that it's a non-disabled person's fault to suffer, but that our hyper-ableist culture tells us all these ways that you should be, and then parenting knocks that all over. And disability has done some of that work of getting rid of those myths ahead of time.

Lisa: I have totally seen that. I've been, as an Auntie, alongside a lot of friends and family members as they've had new babies in the house. In almost every situation with people who are not disabled having kids, it just flips their life over. They just, especially with the first child, have no idea what's about to hit them.

I've been in situations where somebody's telling me, "Oh yeah, I’m going to have a C-section on Tuesday and then we're moving on Thursday." Or, "The baby's going to be born and then I'm going to come right home and receive a big delivery of appliances because we're remodeling our kitchen." And I'm thinking to myself, "That's not going to happen. You're going to have to reschedule that." And then they do have to reschedule. Often there's a lot of distress around that transition.

So it was so striking to me when you wrote about all these non-disabled parents reporting that exact experience in their first week of parenthood, and then meanwhile all the disabled parents being like, "It was cool, it was fine."

Jessica: I was so shocked when I started doing those interviews because I knew I adjusted to parenthood very easily and I thought either I had a false memory or that it was just me.

Lisa: And I love the point you made a minute ago that it's not non-disabled parents' fault. The society we live in tells us that we are supposed to always be able to keep going. It's true when people die and it's true when people have babies and it's true whenever we have any major life change – a divorce or a move or whatever. We believe we're supposed to just continue powering through. It's an incredibly ableist expectation.

Jessica: People feel like a failure when they can't power through and can't be hyper-independent. It’s a confrontation with how messed up that system already was.

Lisa: That’s a great segue to talk about one of my favorite topics here at The Auntie Bulletin, which is interdependence. You've been talking about the independence expectation that's put on all of us. In particular, you write a lot about disabled parents who are declared unfit because they're not independent enough.

So I wonder if you could talk about the narrative that gets put on disabled people, around what counts as fitness and how that relates to independence. And then you make this lovely argument that disabled people are actually better at accessing interdependent networks.

Jessica: In 22 states currently, parental rights can be terminated or a custody change can happen if the parent is disabled – without evidence of abuse. So it's like, does the disability make the judge and the social worker think this child will suffer? If so, a child can be removed. And the way that's judged is basically, can this person parent alone? Do they need help? Do they need support?

The need for help is not reserved for disabled people and it doesn't make you a worse parent. We all need help. Lower-income people lose custody more often because the need for support when you're disabled or lower income becomes so much more apparent and so immersed in bureaucratic systems. But actually every parent uses childcare and public education and after-school care or daycares or parents or Aunties who live close by. Or they use DoorDash and Instacart or all of these app-based help systems. Needing help is a part of being a parent, but it's weaponized against certain groups of people. Instead, having a way of marshalling help should be celebrated, particularly with disabled people.

There are people called mandated reporters, which are teachers, doctors, social workers, nurses, police officers, daycare providers. If any of those people suspect that someone is an unfit parent, they're required to report it. Disabled people interact with mandated reporters a lot more than non-disabled people because we tend to be lower income. We rely on food subsidies or Social Security Insurance or home health aides.

But most of the people in mandated reporter positions are not disabled, so it's non-disabled people making a judgment in an ableist society about if a disabled person is a good enough parent, and then reporting it. Almost no social workers are disabled. The judges who make the final ruling aren't disabled. The whole system is just – I keep pausing because I'm trying not to curse. It starts from the fact that disabled people need help, and from there it totally unravels.

Lisa: You wrote about your personal experience discovering how training programs to access these professions are super ableist and it’s really hard to get through them. People with disabilities can't become social workers, doctors, attorneys, and so forth because the programs aren't accessible.

Jessica: Exactly. In my case, I am a social worker, but I had to delay it a year because the first field placement I tried wasn't accessible. On my first day they said, "If you have a wheelchair, you're going to take up elevator space from people who really need it."

There was no other accessible placement. And then my graduate program said, "I think you might just be too disabled to be a social worker." I called all these disability rights organizations and was trying to figure out how to do it. I was living in Oakland, and I called the field placement office at UC Berkeley. I was at Columbia, but I called UC Berkeley and asked them to help me find a placement.

Finally, a professor who had a lot of sway at the school took me under her wing and she created a virtual field placement for me so that I could get my hours and graduate. I only got my MSW because someone with power went to bat for me. I almost didn't graduate, and not for lack of effort, but because the program was so profoundly ableist.

Someone in the administration even said to me at one point, "You look too good to be disabled." I mean, what they actually said is, "You're too pretty to be as disabled as you say you are." What does that even mean?

Lisa: Oh my god, that's so gross in so many different ways.

Jessica: I was just trying to get a graduate degree!

Lisa: Your experience is such a vivid illustration of how inaccessible these professions are, which then become the gatekeepers for disabled parents to be able to parent their own children.

Jessica: So then non-disabled people have a tremendous amount of power and take children away. If I were to interview a disabled person, which I have done many times, and hear about how they parent, I am much more likely to think, "Oh, my God, this is brilliant. This is innovative. This is a model for what parenting should be." But if a non-disabled person does that same interview, it might make them uncomfortable. They might think, "Is this okay?"

Exposure really does impact how we judge things. Representation actually impacts laws. It impacts practices. It impacts actual real experiences and rights.

Lisa: You have this beautiful quotation toward the end of your book. You write, "What if we judged every parent by how good they were at marshalling help for the sake of their children? If that were the metric, disabled parents would be among the best."

This is so true and spot on, and it also makes me think about the role of Aunties in helping to almost normalize and provide representation of more wholesome ways of doing families, which disabled people are leading the way on, and so are Aunties.

Jessica: I think that's exactly right. You're a demonstration that there's nothing shameful about needing more than just one or two parents, that we all need help. And that's not a deficiency in parenting. It's better.

Lisa: It's way better! I'm planning a post about families without Aunties. Long story short, families without Aunties are on the ropes. They are struggling hard. There are very few exceptions to that, unless maybe you have a ton of money and you can just hire Aunties, basically.

Jessica: My eldest was rock climbing for a while, and I can't rock climb, obviously. I also couldn't enter the place where the bouldering walls were because it's cushioned. You can't make a floor safe for someone falling from the walls and also make it wheelchair accessible. I couldn't enter that space, but my kid needed an adult with her in this gym.

What ended up happening is I exchanged numbers with a bunch of other climbers. None of them had kids, but they would meet me there and help her climb and we developed these friendships with a bunch of different adults. It was beautiful. It was absolutely stunning. I would sit there 20 feet away and usually work on some project or read a book or do something while she was forming this independent relationship with an adult and developing this hobby. And I don't think it was a loss for her that I wasn't the one helping her climb. I think it was expanding the people who knew and loved her. I think that's fine.

Lisa: It’s not just fine, it's a protective factor in her life to have more loving adults. And I think it really illustrates the point that you're making that a mandated reporter who doesn't know what they're looking at might be like, "This woman is letting strangers teach her kids how to climb rocks. Who is that man? I need to report this woman to Child Protective Services." That is actually how these things go down.

Jessica: Yes. And they might think that I couldn't be there keeping her safe. But actually I was keeping her safe.

Lisa: Jessica, it's been so awesome to talk to you. I have just loved this conversation. And I am so grateful to you for talking to me and sharing your wisdom with all the Auntie Bulletin readers.

Jessica: Thank you so much for reading the book and including me here. I'm so amazed people actually attend Lives!

Lisa: Right? It's always a surprise to me when people actually show up, yet here you all are! Thank you, everybody, for being here. I hope that if you have not yet read Unfit Parent that you will go out and do that right away. You can get it from your public library or your local independent bookseller or if you have to buy it online, don't buy it from Amazon! How about bookshop.org? That's a great place to get it.

And Jessica, you also have a newsletter, right?

Jessica: It’s called Whatever What Is. It's a poem by Galway Kinnell that I've had on my wall a bunch over the years. The name of the poem is "A Prayer," and it says, "Whatever what is is is what I want. Only that. But that."

Lisa: I love it. That's beautiful. I had read elsewhere that you like to share poetry, so I'm glad that we got some.

Jessica: Yeah, I'm always trying to find a way to sneak a poem in.

Lisa: Thank you so much, Jessica!

Related Reading from The Auntie Bulletin

Nothing Sold, Bought, or Processed

The Auntie Bulletin is an ad-free, feminist, anti-capitalist publication that will never try to sell you anything and donates 100% of revenue from Bookshop.org affiliate links to organizations supporting vulnerable kids. Through the end of September 2025, the recipient organization is Treehouse Foundation. Look for receipts in early October.

If today’s post made you think or helped you out, please take a moment right now to become a paid subscriber. This newsletter is a form of carework and carework advocacy, and it’s how I make a living.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end! You get the secret scoop that if you can’t afford a paid subscription due to financial hardship, you can reply to this email to let me know and I’ll comp you a 12-month paid tier subscription, no questions asked.

Share this post