Today’s post is a follow-up to last week’s, in which I argued that mature people — actual, functioning grown ups — share. I argued we should model everyday resource sharing so that the kids in our lives view sharing among adults as normal and good, and grow up to be practicing sharers themselves. This week, I’m turning toward another key way we can help kids become lifelong sharers: by actively teaching them what sharing entails.

My Aunt Debbie has many hobbies, and one of them is collecting and polishing small beach rocks.1 A few years ago, she put a bunch of rocks in a bag for each member of our (large) extended family and gave them to all of us for Christmas. My partner got one and I got one, so our household now has two small bags of polished rocks.

They are the most coveted toys we own.

There have been near-fistfights over these rocks. Children have been hauled away kicking and screaming, absolutely losing their minds with rage over being separated from, or not being allowed to hoard every one of, these rocks.

We tell the kids to share the rocks to no avail. An older child grabs the most cherished rocks, as well as a greater number overall, for himself. A younger child shrieks and pulls hair and grabs the highest-status rocks the first chance she gets, and then runs away and hides with them, pursued by her older sibling bearing more of the cherished objects – objects which are, of course, also weapons.

Over time, I’ve had to become more and more purposeful about not just telling kids to share the rocks, but actually teaching them how. They need practical strategies for slowing down and not trying to murder each other, and then figuring out how to distribute the precious commodity in a way that feels fair to all. When it goes right, you can actually observe everyone’s bodies relax in real time – children and adults alike – and a minute later the kids are playing happily together (or at least they’re playing harmlessly and in parallel).

What is the Difference Between Telling and Teaching?

Before starting The Auntie Bulletin, I was a teacher and a teacher educator for about twenty years. One of the most important things new teachers learn is that you can’t just tell students to perform a skill, you have to teach them by showing them how, helping them discover why, and giving them lots of opportunities to practice the little micro-skills that make up the big skill. Novice teachers – and, unfortunately, a certain percentage of veteran teachers as well – tend to assume that assigning a task to students will suffice. “Draw a map of your neighborhood.” “Define the word ‘exaggerate’ and use it in a sentence.” “Create a poster depicting the life-cycle of a Chinook salmon.” “Divide a fraction by a fraction by multiplying the reciprocal.” “Read Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and write three discussion questions for class tomorrow.”

Teachers assign tasks like these all the time; merely assigning, however, does not predict student success. In classrooms where students successfully come to understand what they’re doing and why, they have actually been taught the skills or tasks they’re assigned.

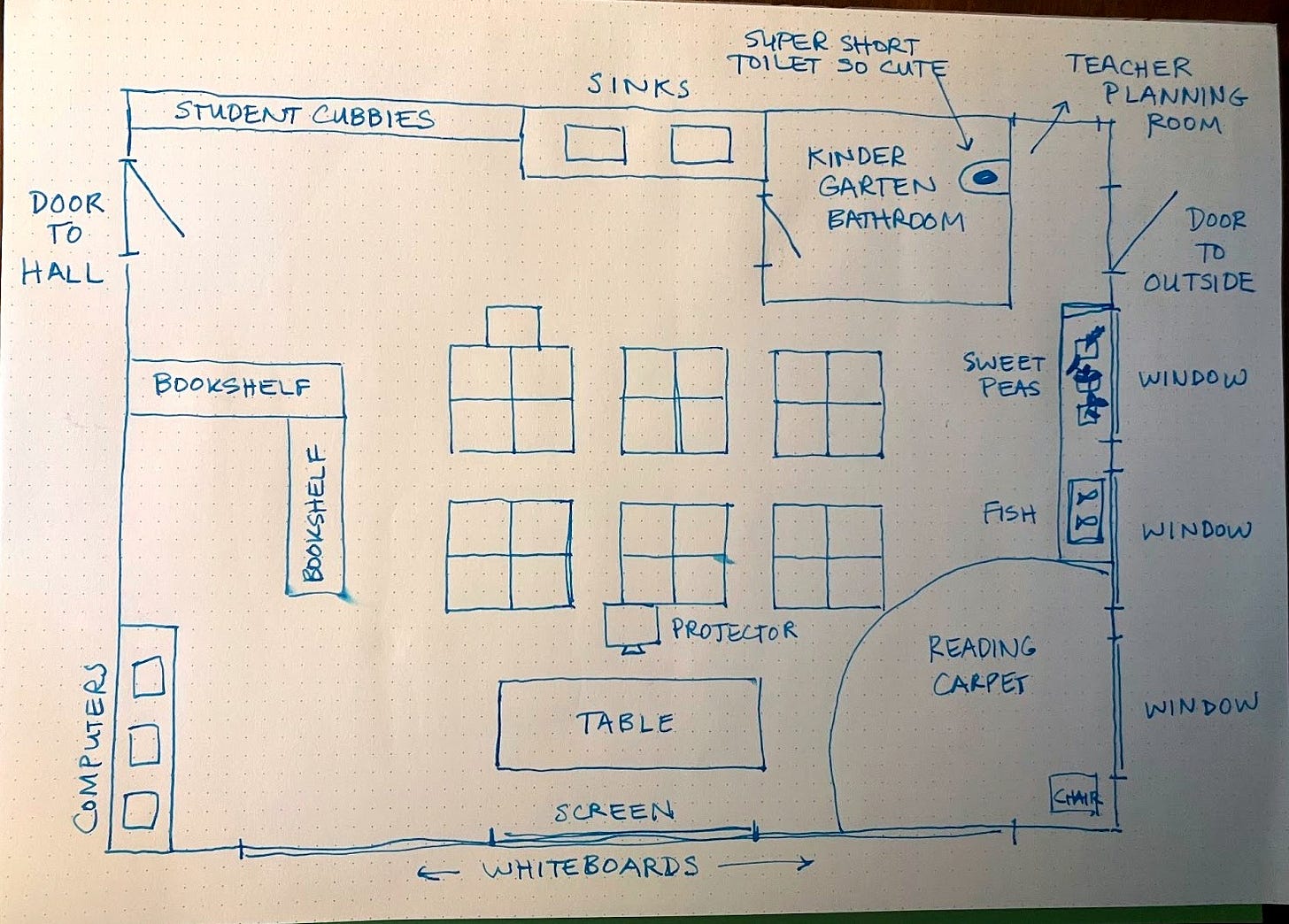

So rather than just telling her first graders to draw a map of their neighborhood, Ms. Lee first shows her students a bunch of simple, colorful maps and helps them understand that maps represent what we would see if we were a bird flying high above. Then she draws a map of their classroom, right in front of students, in real time. She thinks aloud about her process. “Okay, I’m going to put the door over here in the top left hand corner because we have to fit the whole classroom on the paper so I want to leave a lot of room! I will draw a line for the door because I’m pretending I’m high up above the door, looking down, and that’s what a door looks like from the top. Right next to the door, I will put your cubbies. Over here on the other side of the paper, the right side, I will draw the windows, because in our classroom the door is on one side and the windows are on the other. See? I can hold it up and here is the door and here are the windows and where they are in our real classroom matches where they are on our map.”

Among ourselves, classroom teachers call this the “I do” step: I, the teacher, show you how to do the thing and think aloud as I go along to make my thought process visible to learners.

Now Ms. Lee asks, “Where should I put our classroom sink? Turn to your neighbor and find out what they think about where we should put the sink on our map, and then I’ll get some volunteers to tell us their ideas.” After the students talk to each other for a minute, Ms. Lee gets a bunch of their suggestions. She takes all of their proposals seriously, including the ones that aren’t correct. She makes space for the students to think out loud together. Maybe there’s a cute little back and forth among students about whether the sink goes at the top of the paper or the bottom. Maybe some kids get up and walk around and point to try to show which position is correct. Ms. Lee lets them think it out, and gives them some nudges if they need them, until the class can determine that the sink goes at the top of the paper, i.e., the back of the classroom.

This is what teachers call the “we do” step – together, we reason our way through the task and get some practice together.

Now Ms. Lee asks kids to draw their own maps of the classroom. They should put at least 10 things from the classroom on their map, including their own desk and cubby. Ms. Lee cruises around the classroom and checks out kids’ emerging maps. She gives them encouragement when they’re on the right track (“ooooh, putting our birthday chart is a nice idea!”), and asks questions that help them course-correct where needed. “Hmmm, I see you have the fish tank over here by the cubbies, but I’m looking at the fish tank and it seems like the sun is shining on our fish right now. Does the sun reach all the way over to the cubbies?”

Teachers call this the “you do” step – now that I, the teacher, have modeled the task and we have all thought more deeply about it together, you, the student, can try it on your own and I will help you if you need it. Tomorrow – now that we are all cartographers – we’ll be ready to try drawing a map of the neighborhood.

I do, we do, you do. I show you, then we do it together, then you try it on your own. We in the teaching biz call this a “gradual release of responsibility,” and it is one of the basic, deep processes of human learning. True, we don’t always get to have the “we do” step in daily life – friendly mentors and teachers aren’t always alongside us to help us learn everything we need to know – but the “I do” and the “you do” are indispensable. Humans basically can’t learn any skill without first observing others and then trying it out for ourselves.

Okay, so, let’s talk about teaching kids to share. Like drawing a map of the classroom or neighborhood, sharing with others is a skill with component parts. We have to be able to recognize that we’re feeling possessive about a resource, take a pause to get hold of ourselves, and then come up with a plan to share the resource in a way that will meet everyone’s needs. Like any skill, sharing is best learned through observing others in action, trying it with help, and then trying it on our own.

Teaching kids to share is a gift that Aunties can give those kids, and their parents, and the world, and ourselves.

Teaching kids to share helps the kids themselves because fighting over resources isn’t fun. Kids have a much more pleasant experience when they don’t have to fear that they will miss out because they know they’ll get a fair turn, and when they aren’t attacking or being attacked by their fellows. Go figure.

Teaching kids to share helps the parents because they are inevitably super burned out on their children’s squabbles over rocks. Letting somebody else deal with it this time lets parents conserve energy for the bedtime routine or whatever’s coming up next.

Teaching kids to share helps the world because kids who learn to share small things grow into adults who can share big things — who show up for their communities as well as for other people’s children, who advocate for social safety nets, and who understand themselves as stewards of the earth and of future generations.

Teaching kids to share helps Aunties ourselves because the more we practice, the more successful we become. When it works (which won’t be always), helping kids learn to navigate conflicts and show care for one another is straight up joyful. It is fun. It makes you feel like you are living a good, happy, and meaningful life.

So let’s do that, yeah?

After the paywall, I’ll describe some practical everyday strategies for teaching kids to share – riffing on the “I do, we do, you do” model.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Auntie Bulletin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.