The Limit-Embracing Auntie

I'm barely holding it together (again), but prioritizing the kids in my life helps.

One of the only places I’m going for my news these days is Anya Kamenentz’s sane, stabilizing weekly round-up, “What Really Happened Last Week.” Aiming to “model healthy, balanced news consumption,” Anya sums up five important stories from the past week, including at least one piece of good news. Her news roundups are paywalled, but you can access them for free for a year when you upgrade to a paid annual subscription to The Auntie Bulletin.

In other news, this Thursday I’m going live on Substack with Rosie Spinks to talk about kinship and community-building in a time of collapse. We’ll explore the work of tending, nurturing, and healing even as things fall apart around us. I don’t think either of us has simple answers, but I will say that Rosie’s work always makes me feel hopeful.

You can tune in live on the Substack app on Thursday, April 10 at 12pm PST // 3pm EST // 8pm UK time (find your timezone). Our conversation will also arrive in your inbox with your regularly scheduled Auntie Bulletin this Friday. If you have questions for me and Rosie, let us know in the comments or reply to this email.

Now Let’s Get To It

Aunties, this week I had big dreams. I made big promises. I was going to write a really great how-to on befriending our elders, and I have a lot of things I’m excited to say about this topic. I still will, sometime soon.

But on March 22, my dear friend Chris was killed in a car accident. I started a new part-time job around the same time,1 and the workload has been bigger than I expected. So I’m weary, and I’m sad, and I’ve been trying to write the befriending elders post for several days but I can’t get ideas to come together. I’m putting a pause on it.

I’ve lost people before. I lost my grandparents, including the two beloved grandmothers I wrote about last week. I lost four pregnancies in quick succession. Over the course of my 20s, I lost two of my brothers to suicide, and let me tell you that was brutal.

So I guess I thought I knew about loss by now. I thought I had a good grip on how much rest I would need before I’d be ready to focus on work again. I was naive, Aunties. I was delusional. I underestimated how much time I would need. Grieving is very hard work and it takes a lot out of you. I had forgotten.

So today I’m going to share a lightly-edited post that I originally published in October 2024, about acknowledging my limits and taking refuge in relationships with the people I love.

On Embracing Limits

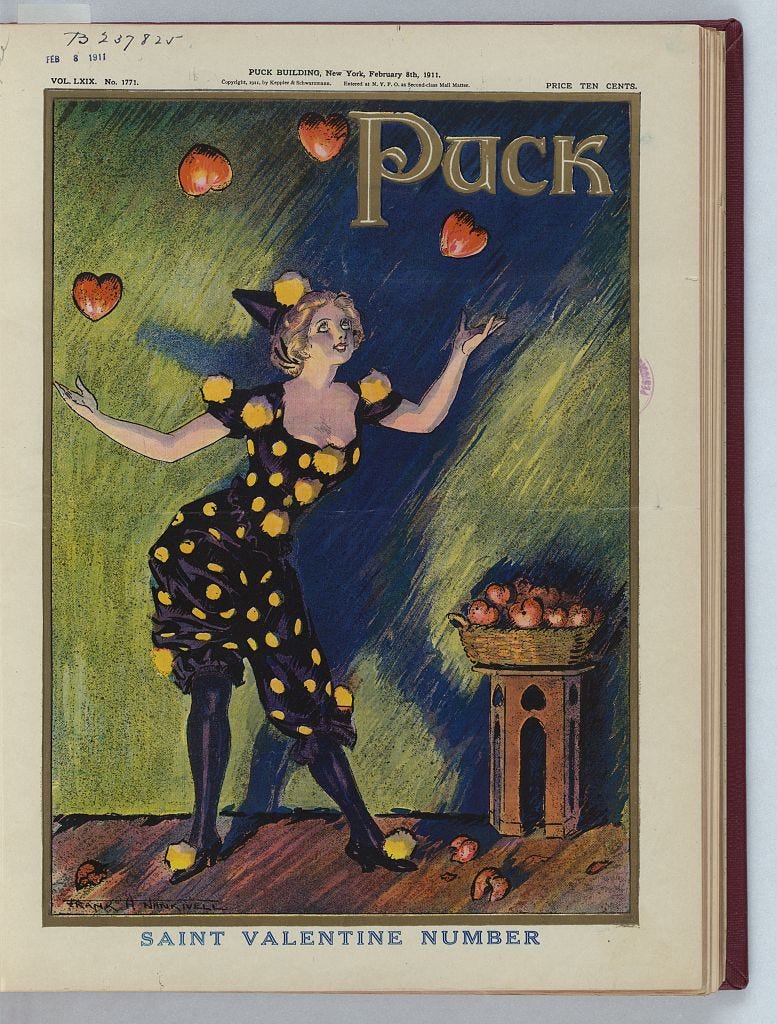

A few years ago, I learned to juggle. It was a big accomplishment for someone like me, who grew up with a persistent self-narrative that I am not coordinated, not good with throwing and catching. My partner is an expert juggler, however, as well as a patient teacher. First he showed me how to successfully throw and catch one ball, over and over and over. Then two. I practiced standing facing a wall so that balls that arced outward would bounce back in my general direction, often such that I could actually catch them and keep going. I became competent at juggling two balls for a long period – a big deal given my aforementioned self-concept as an uncoordinated person. When I introduced the third ball, it took weeks of practice before I could reliably keep all three in the air – but Aunties, I got it down. I can totally juggle.

Okay, but is it reasonable to try to go from juggling two balls straight to juggling four?? Do not pass three, do not experience competence? Because that has been my week. Just to be clear, for people who are not married to expert jugglers, juggling four balls entails juggling two balls in one hand, juggling two balls in the other, and then weaving it all together using magic. “Four,” my partner tells me, “is exponentially harder.”

Boy, is it ever. I’m currently in the midst of an enormous ramp-up of responsibilities, a massive acceleration of pace, and earlier this week the overwhelming flood of new demands had me near panic. Nevertheless, in the midst of my frenzy of activity, a kid I love unexpectedly stopped by for a couple hours, I paused everything to hang out with her, and it was the right choice. Balls were dropped, but the most important one – my community – stayed up.

A Hard Truth

Let me sketch where I’m at in life. For the past year, I’ve been off work due to a chronic health condition, and it’s been an enormous gift. I’ve rested, cared for my body, and had space to attend to what I care about the most: a little community organizing, a labor-of-love research project, and showing up for my friends and family. I’m unfortunately attached to values like productivity and responsibility, so my slowing down came with a degree of self-recrimination, but Katherine May’s book Wintering was a big help. She writes:

“The tree [in winter] is waiting. It has everything ready. Its fallen leaves are mulching the forest floor, and its roots are drawing up the extra winter moisture, providing a firm anchor against seasonal storms. Its ripe cones and nuts are providing essential food in this scarce time for mice and squirrels, and its bark is hosting hibernating insects and providing a source of nourishment for hungry deer. It is far from dead. It is in fact the life and soul of the wood. It’s just getting on with it quietly. It will not burst into life in the spring. It will just put on a new coat and face the world again…. Life goes on abundantly in winter — changes made here will usher us into future glories.”

For the past twelve months, I channeled the life and soul of that tree, and – to mix metaphors – I kept two balls in the air, and it’s been mostly lovely. It’s also financially unsustainable.

Currently, I’m exploring how to make a living while also having enough flexibility in my schedule to take care of my physical needs, so this fall I committed to several small-to-midsize jobs in the naive belief I’d be able to juggle them, with space in between for doctors appointments and physical therapy. Now, of course, here I am with a weekly newsletter, a university class to design and teach, and two academic research projects – four balls. I need to keep taking care of my body, which takes (a lot of) time. I need to keep taking care of myself, which takes (a lot of) rest. And I need to keep showing love to my people, or what is this one wild and precious life for?

On Tuesday I found myself up against the hard, bare truth that I simply cannot do everything I intend to. This past Monday I started teaching — a bumpy start to be honest — and by Tuesday evening I hadn’t even begun my Auntie Bulletin post for the week. I was running on fumes and self-flagellation, determined to publish something, anything before I went to bed, to not drop cadence so early in my newsletter writing career. That’s when a child I love unexpectedly stopped by my house for a visit, and I had to decide whether or not to send her home.

Earlier that very day, I had started reading Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. The average human lifespan is about four thousand weeks, Burkeman explains, and while our tasks and commitments and responsibilities will keep arriving in an unending, infinite flood, the time we have in which to address them is “strictly finite.” Rather than despair, Burkeman encourages us to embrace these limits. Once we accept that we definitely won’t have time to do everything we want to do, we can stop beating ourselves up for failing, and “focus instead on building the most meaningful life [we] can, in whatever situation [we’re] in.” He writes:

Every decision to use a portion of time on anything represents a sacrifice of all the other ways in which you could have spent that time, but didn’t – and to willingly make that sacrifice is to take a stand, without reservation, on what matters most to you.

Having just read that, I was able on Tuesday night to drop all my urgent tasks, put down my Auntie Bulletin publishing timeline, and spend a couple of hours with a wonderful kid.

The next day, I did some reflection and recalibration. I identified a few short-term and medium-term commitments that I can either slow down or let go. I realized I need to renege on a major commitment I’ve made, and some people may be frustrated and inconvenienced as a result. I’m making the choice to let that happen – to drop that ball – in the interest of taking a stand on what matters most to me. This is what Burkeman calls “the limit-embracing life.” We let go of our predetermined plans for success. We “respond to the needs of our place and our moment in history.” It’s scary, and it’s hard, and it’s necessary.

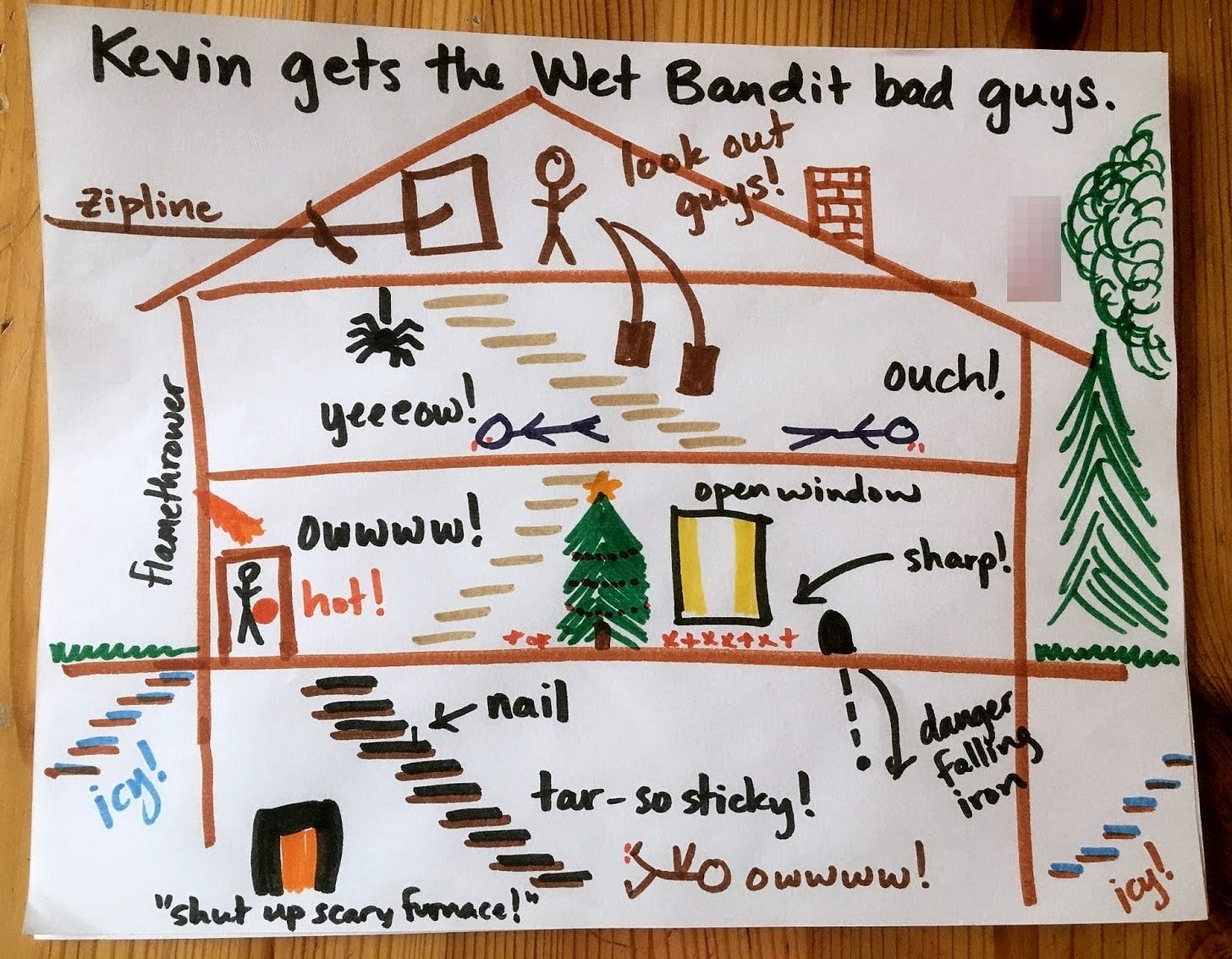

Drawing scenes from Home Alone with a kid on a Tuesday evening may not seem like a life-defining act, but I argue hyperlocal community-building *is* responding to the needs of history. Every time we prioritize people over productivity, we cultivate an understanding of what matters – an understanding that will serve us and our communities throughout our lifetime. We practice building connection and capacity, the core requisites of social change. We reject the expectation of the endless hustle, and we model that rejection for others, including kids. We require ourselves to find a better way.

Three Recommended Reads

At The Double Shift, Katherine Goldstein wrote about the Care Can’t Wait bus tour, “an effort by Caring Across Generations to rally supporters in swing states around care as a voting issue.” At the tour stop she attended, Goldstein met a young man in his 20s who became the primary caregiver for his mom when she was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s.

Stites’ mom passed away in 2022, about four and a half years after her diagnosis. While caring for her, he maxed out his student loans, to the tune of $40,000, while going to grad school online so that he’d have enough money to care for them both. He describes his mother's illness as heartbreaking and devastating, and he continues to advocate after her death because he wants people to know “how much purpose that experience gave [him].”

“I feel closer to the human experience,” he told me. “I wouldn't trade that experience of providing care as lonely as it was. It made me a stronger person.”

Men and childless people in their twenties aren’t who you expect on stage at a care rally. But stories like Sam’s show that becoming a caregiver can happen to anyone at any age.

Finally, The Cute Kid Video of the Week

Did you know babies babble in American Sign Language?

Nothing Sold, Bought, or Processed

The Auntie Bulletin is an ad-free, anti-capitalist publication that will never try to sell you anything and receives no money from affiliate links. I can only offer it if readers like you make modest donations to keep the lights on. If you appreciate what you read here, please take a few seconds right now to become a paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end! You get the secret scoop that if you can’t afford a paid subscription due to financial hardship, you can reply to this email, shoot me a message in the Substack app, or email me at auntiebulletin at gmail dot com and I’ll comp you a 12-month paid tier subscription, no questions asked.

The Auntie Bulletin isn’t paying the bills yet. Someday, I hope.

There’s something so radical—and so human—about choosing presence with a kid over perfection with a deadline. I needed the reminder that love isn’t a thing we squeeze into the margins, but something worth rearranging everything for.

Also: I hadn’t heard that Burkeman quote before, but it reframed everything. Especially the line about every choice being a stand for what matters most. What you wrote here is a stand—and I’m grateful to be one of the readers it reached.

I’m so sorry for your loss. I hope you can find ways to take time for grief.

(And I think “ATAP” might be either “A Trap” or “Attack” given that it follows “Shhh” :))